RAF Centenary:

Radcliffe on Trent’s WWI Air Servicemen

Bristol Fighter, as flown by Lieutenant Charles Geoffrey Claye

The Shuttleworth Collection’s Bristol F.2B Fighter

April 1st 2018 marked the centenary of the RAF, formed from the amalgamation of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) in 1918. At the beginning of the war the flying services carried out valuable photographic reconnaissance alongside manning and operating observation balloons. Their role soon developed to include aerial battles, strategic bombing and strafing the enemy. The aircrew of the RFC, RNAS and RAF showed immense courage flying in open cockpits under freezing conditions, over enemy territory and without parachutes. When the war ended, over 9000 aircrew had been killed or were missing in action and over 7000 had been wounded. More pilots died in training than in combat and one in four pilots and observers did not survive.

The Royal Flying Corps, established in 1912, was a corps of the army and comprised a military and a naval wing, a Central Flying School and the Royal Aircraft Factory. The RNAS, existing from 1st July 1914 to 1st April 1918, was initially the naval wing of the RFC but administered by the Admiralty. In August 1915 it became an integral part of the Royal Navy until the founding of the RAF in 1918. The RFC, RNAS and later the RAF were organised into squadrons, wings and groups.

There was a great variety of roles within each section of the air services and a marked difference between the work of aircrew and ground crew. Many of the aircrew were young officers who had recently completed their education and been commissioned in the army. Officers entered the Royal Flying Corps either by transfer from the army or by joining a Special Reserve, which did not require military experience. Before July 1916 those wishing to enter the RFC as pilots had to buy a Royal Aero Club aviators certificate for £75; if accepted the money was refunded. The requirement meant that the first WWI pilots were men able to afford the licence who were then given rudimentary training. The RFC began regulating flight training standards in early 1916 and trainee pilots were expected to fly fifteen hours solo before active service but the demand for pilots and insufficient resources meant that by early 1917 many new pilots were inadequately prepared for the ‘war in the air’. Casualties rose sharply. In contrast to the aircrew, ground crew were often working in manual jobs before the war (for instance as joiners, electricians, engine fitters and so on) and had already acquired skills which were essential for the maintenance of aircraft. Several were married men with children.

Eighteen men from Radcliffe on Trent and Holme Pierrepont were deployed in the various air services during the war. Their experiences embrace different roles and reveal the multi-faceted nature of the service. Three men were observers/pilots and two were ground crew on the Western Front. One was an infantry officer who became an air service instructor in England after serving in France. Six men were ground crew on various bases in England, three of them in the RNAS. Six other men were still training with the RAF when the war ended and did not see active service.

Observers, pilots and instructors

At the beginning of the war the Germans had the advantage in the air. Their Fokker monoplane was the first aircraft to use a synchronised machine gun, achieving air superiority from late 1915 through the spring of 1916. Allied fighters were then introduced able to deal with the Fokker. In 1917 new and superior aircraft such as the Albatross D.III restored German superiority at the Battle of Arras (“Bloody April”). The introduction of the SE5 and the Sopwith Camel that year then meant that combats became more even handed.

At the beginning of the war the Germans had the advantage in the air. Their Fokker monoplane was the first aircraft to use a synchronised machine gun, achieving air superiority from late 1915 through the spring of 1916. Allied fighters were then introduced able to deal with the Fokker. In 1917 new and superior aircraft such as the Albatross D.III restored German superiority at the Battle of Arras (“Bloody April”). The introduction of the SE5 and the Sopwith Camel that year then meant that combats became more even handed.

William Ritter, Norman Saward and Charles Claye were three officers from the Radcliffe on Trent locality who fought the war in the air. William and Norman were in the University of Nottingham Officer Training Corps (OTC) and Charles had been in the OTC at Charterhouse School. William and Charles were seconded to the Royal Flying Corps from the Army Cyclist Corps and Sherwood Foresters respectively. On joining the RFC they became observers (there was no formal training for observers until 1917). When certified as fully trained, they wore the half wing brevet on their uniform, as seen on the photo of William Ritter. Observers accompanied pilots in two seater planes, most of which did not have dual controls so they could not take over if their pilot was unable to continue flying. Norman transferred from the Royal Artillery and soon became a pilot.

William Ritter lived at Chestnut Grove, Radcliffe on Trent. He was described by Captain Clive from the University of Nottingham OTC as ‘a remarkably clever boy who had done some extremely good work at map enlargement and reconnaissance, spoke French and German fluently and knew Belgium, North France, and Germany well’. He was mentioned in dispatches in June 1916 while serving with the army and was then attached to the RFC in December of that year. In June 1917 he was killed in a flying accident which did not involve enemy action; he was buried at Varennes Military Cemetery, France. He was flying with No.15 Squadron.

On September 9th 1917 Lieutenant Norman Saward was involved in a dog fight over Belgium in which he was shot down. Norman, the son of the vicar of Holme Pierrepont, had been with the RFC for only two months and was nineteen years old. The combat report of the incident by Flight Commander Captain Clive Collett, 70 Squadron, includes the following information:

We patrolled as instructed between Gheluvelt and Houthulst Forest. When over Gheluvelt at 5.10 p.m. we attacked three 2-seater enemy aircraft and after a short exchange of shots two made off in an easterly direction. The formation engaged the remaining machine hotly and I got off a good burst at him. Lt. Saward also fired off on this machine and it went down entirely out of control. We did not see it crash as it disappeared in the haze. The formation then patrol up to Houthulst where three more 2-seater enemy aircraft were engaged at 5.25. I got onto the tail of one of these and drove him down from 10,000 feet to 4,000 feet. The machine was entirely out of control with smoke coming from the fuselage and from 4,000 feet I saw this machine crash north-east of Houthulst Forest … Lieutenant Norman Cuthbert Saward was unfortunately taken prisoner when his Sopwith Camel (B3916 ) crashed behind enemy lines. (source: www. airwar19141918)

‘Replica Sopwith Camel painted in the colours of New Zealand-born pilot Captain Clive Collett who was credited with being the first ace to achieve a victory while flying a Sopwith Camel’ (image and information from www. aviationfilm.com/shorts/camel/index.html).

Captain Collett was awarded a Military Cross for the incident leading to Norman’s capture; he was killed three months later test flying a captured Albatross in Scotland. Norman was held at Schweidnitz POW camp near Schleisen in east Germany until the end of the war. After repatriation in January 1919 he continued his career in the RAF. In 1924 he was serving on the Indian North West Frontier and flew one of two planes purchased by the Afghan government from Simla to Kabul. There he was decorated with the Order of Izzatt, first class. He became a Wing Commander in 1938 and served in WWII.

The RFC’s training organisation became more sophisticated in 1917 with the formation of a Training Brigade and schools to teach air fighting, bomb dropping, night flying and other skills. The new flight training had a significant impact on reducing fatalities. Lieutenant Charles Claye had flown on the western front and became involved in the training programme. He spent his childhood at Radcliffe Hall before his parents moved to Nottingham. He joined the 2/5th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters in October 1914 and was sent to the Front in August 1916. In March 1917 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps where he trained as an observer at the School of Aerial Gunnery, France. He was appointed a flying officer in April and was attached to No. 48 Squadron where he flew Bristol F2 Fighters from April 3–May 9 and then the De Havilland DH4 from July–November 1917 (the DH4 was a light two-seater day bomber plane). Charles was wounded twice and returned to England in November on home leave. In January 1918 he was given a post in England as an instructor in aerial navigation and bomb dropping at Hythe School of Aerial Gunnery, Kent but asked in April to be transferred back to the Front. Charles was killed on July 5th 1918 during a bombing raid while acting as an observer in a De Havilland D.H.9, a plane often subject to engine failure and soon replaced by the D.H.9A. Following his death, his commanding officer wrote, ‘There are few men, I think, who would deliberately have given up the chance of a ‘soft job’ in England to go out again, the second time, as observer. He was doing most valuable work, as for some time he was our only experienced observer’.

The RFC’s training organisation became more sophisticated in 1917 with the formation of a Training Brigade and schools to teach air fighting, bomb dropping, night flying and other skills. The new flight training had a significant impact on reducing fatalities. Lieutenant Charles Claye had flown on the western front and became involved in the training programme. He spent his childhood at Radcliffe Hall before his parents moved to Nottingham. He joined the 2/5th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters in October 1914 and was sent to the Front in August 1916. In March 1917 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps where he trained as an observer at the School of Aerial Gunnery, France. He was appointed a flying officer in April and was attached to No. 48 Squadron where he flew Bristol F2 Fighters from April 3–May 9 and then the De Havilland DH4 from July–November 1917 (the DH4 was a light two-seater day bomber plane). Charles was wounded twice and returned to England in November on home leave. In January 1918 he was given a post in England as an instructor in aerial navigation and bomb dropping at Hythe School of Aerial Gunnery, Kent but asked in April to be transferred back to the Front. Charles was killed on July 5th 1918 during a bombing raid while acting as an observer in a De Havilland D.H.9, a plane often subject to engine failure and soon replaced by the D.H.9A. Following his death, his commanding officer wrote, ‘There are few men, I think, who would deliberately have given up the chance of a ‘soft job’ in England to go out again, the second time, as observer. He was doing most valuable work, as for some time he was our only experienced observer’.

As training for observers and pilots became more rigorous, the need for instructors increased. Captain William Ecob was one of those appointed, due to his university qualification in topography and teaching experience. He was another member of the University of Nottingham OTC and had interrupted his degree to enlist in 1914. He served with the Green Howards on the western front for over two years then returned to England in September 1917 where he was diagnosed with neurasthenia. William was transferred to Hastings 6 School of Aviation in August 1918 where he served as an instructor for No.5 Cadet Wing until the autumn of 1919. His descendants recall that while at Hastings he used to play tennis with the future King George VI who was also stationed there. After the war William completed his degree and had a successful career in the chemical industry.

As training for observers and pilots became more rigorous, the need for instructors increased. Captain William Ecob was one of those appointed, due to his university qualification in topography and teaching experience. He was another member of the University of Nottingham OTC and had interrupted his degree to enlist in 1914. He served with the Green Howards on the western front for over two years then returned to England in September 1917 where he was diagnosed with neurasthenia. William was transferred to Hastings 6 School of Aviation in August 1918 where he served as an instructor for No.5 Cadet Wing until the autumn of 1919. His descendants recall that while at Hastings he used to play tennis with the future King George VI who was also stationed there. After the war William completed his degree and had a successful career in the chemical industry.

Ground crew

Regular maintenance of aircraft was essential for the smooth running of operations and maximizing the safety of pilots and observers; the flying missions could not have been carried out without the hard work and support of ground crew. One of the men from Radcliffe who served in this capacity in England was Lewis Scrimshaw. He enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps in January 1915 as a twenty year old motor engineer. Two years later he was promoted to sergeant and then transferred to the RAF in April 1918 as a sergeant mechanic. By October he was a chief miechanic and classified as an engine fitter. He became a flight sergeant and finished his war service at 95 Squadron, a coastal command station at Shotwick near Chester. He was discharged in 1923 after eight years of service and returned to Radcliffe on Trent and civilian employment as a mechanical engineer and draughtsman. In his retirement he built a functioning model LNER Green Arrow express goods engine which was six feet long and capable of carrying ten passengers.

Royal Naval Air Service

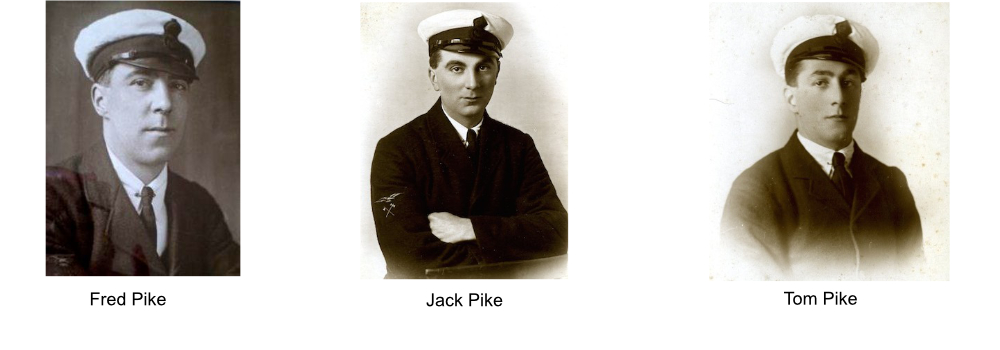

The Royal Naval Air Service had 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons and 727 personnel at the outbreak of WWI and twelve airship stations around the coast of Britain. By 1915 the service not only had seaplanes and carrier-borne aircraft, it also maintained several fighter squadrons on the Western Front. Its stations in the UK were involved in home defence; the principal missions were patrol duties to protect nearby ports and to repel Zeppelin attacks. In Radcliffe on Trent three brothers, Fred, John (always known as Jack) and Tom Pike, left their father’s building and joinery business in 1917 to serve in the RNAS; their older brother Charles was with the Royal Garrison Artillery in France. They were all trained for two or three months at HMS President II, a ship moored near Tower Bridge in London, before being transferred to RNAS stations.

The Royal Naval Air Service had 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons and 727 personnel at the outbreak of WWI and twelve airship stations around the coast of Britain. By 1915 the service not only had seaplanes and carrier-borne aircraft, it also maintained several fighter squadrons on the Western Front. Its stations in the UK were involved in home defence; the principal missions were patrol duties to protect nearby ports and to repel Zeppelin attacks. In Radcliffe on Trent three brothers, Fred, John (always known as Jack) and Tom Pike, left their father’s building and joinery business in 1917 to serve in the RNAS; their older brother Charles was with the Royal Garrison Artillery in France. They were all trained for two or three months at HMS President II, a ship moored near Tower Bridge in London, before being transferred to RNAS stations.

Tom and Jack Pike were sent to RNAS Killingholme on the Humber estuary, which was one of the leading seaplane bases in the UK where 900 servicemen were stationed. Killingholme was an operational station set up to protect local oil installations, ports, repel Zeppelin attacks and was also a seaplane pilot training centre. The Pike brothers were able to put their skills acquired in the building trade to good use. Tom was an air mechanic and joiner repairing the aircraft and Jack was classified as a rigger (responsible for all maintenance work on aircraft excluding engines). It was while at Killingholme they received the news that Charles had been killed at Passchendaele.

When the RAF was founded in 1918, it took over running Killingholme and redeployed many of the servicemen. Tom was transferred to Seaton Carew, Hartlepool in July 1918 as acting air mechanic I. The Seaton Carew base was a detachment of No. 36 Home Defence Squadron of the RFC (and then the RAF), located at RFC Station Cramlington, Northumberland. There was an airstrip at Seaton Carew and seaplanes were kept in Seaton Channel. Jack was transferred to an instruction school (location unconfirmed) where he worked as an air mechanic until 1919. Their older brother Fred went from training on HMS President II first to Chingford aerodrome for three months and then to Eastbourne, where he remained with his wife and children until 1919. He worked at the Eastbourne Aviation Company, which was a RNAS training centre for pilots and a seaplane factory situated between Eastbourne and Pevensey Bay. Around 120 men learned to fly there during the war and around 250 Maurice Farman biplanes were built at the factory (source: www.eastbournehistory.org.uk). One daughter (born 1913) is still alive at the age of 104 and remembers their “digs” and the many aircraft flying overhead. After the war the three brothers returned to Radcliffe on Trent and continued working in their father’s business.

Royal Air Force: continuity and change

The First World War saw the birth of the Royal Air Force and the expansion of the air service from the relatively small Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service to the largest flying organisation in the world in just four years. The RAF inherited over 100 training squadrons and 30 specialist schools. By the time of the Armistice pilots were undertaking an eleven month training course, receiving instruction in all aspects of air fighting and completing an average of 50 hours solo flying. There were six men from the Radcliffe area who were still in training on November 11th 1918. They included Norman Saward’s brother, John Augustus, born 1900, who enlisted as a flight cadet in May 1918. He qualified as a pilot in July 1919 and was listed as an emergency services air force officer in 1939. Gerald Robotham from Radcliffe was appointed a flight cadet in June 1918 and was still in training when he was demobilised in March 1919. Francis Osborne, known as Ralph and born 1902, lied about his age when he enlisted in the RAF in August 1918 (he was fifteen at the time). His older brother Samuel was killed in France the following month. Ralph trained to be a rigger, extended his service in August 1919 and continued with the RAF until 1931. He was employed again by the RAF in WWII and served with them until 1946. He was with 74 Wing in 1939 at RAF Benson, Oxfordshire, the home of two Bomber Command squadrons.

Henry Marshall from Radcliffe on Trent had a different role in the RAF. He was a Chaplain to the Forces (an all officers corps) in the British Army from 1912 to 1918. He was a member of the British peace keeping force in Montenegro in 1913 and awarded a silver medal for bravery by the government. He was stationed for two years on Malta and was attached to the 58th Division when they arrived on the island in February 1915. Henry was promoted to Chaplain to the Forces, 3rd Class, a rank equivalent to Major, and transferred to France in June 1916. He was mentioned in despatches twice: once for actions in Malta and once in France. On 8th November 1918 he received a letter from the Royal Army Chaplains Department informing him that the Chaplain in Chief had applied for his services and the appointment would be notified in the London Gazette (letter held at the National Archives). The appointment appears on the Royal Air Force Chaplains Department List, dated 21st November 1918. Henry Marshall was promoted to Chaplain to the Forces, 2nd Class, a rank equivalent to Squadron Leader, and stayed with the RAF until 1922 when he retired with ill health at the age of thirty-eight.

Henry Marshall from Radcliffe on Trent had a different role in the RAF. He was a Chaplain to the Forces (an all officers corps) in the British Army from 1912 to 1918. He was a member of the British peace keeping force in Montenegro in 1913 and awarded a silver medal for bravery by the government. He was stationed for two years on Malta and was attached to the 58th Division when they arrived on the island in February 1915. Henry was promoted to Chaplain to the Forces, 3rd Class, a rank equivalent to Major, and transferred to France in June 1916. He was mentioned in despatches twice: once for actions in Malta and once in France. On 8th November 1918 he received a letter from the Royal Army Chaplains Department informing him that the Chaplain in Chief had applied for his services and the appointment would be notified in the London Gazette (letter held at the National Archives). The appointment appears on the Royal Air Force Chaplains Department List, dated 21st November 1918. Henry Marshall was promoted to Chaplain to the Forces, 2nd Class, a rank equivalent to Squadron Leader, and stayed with the RAF until 1922 when he retired with ill health at the age of thirty-eight.

The above account shows how some local servicemen continued their links with the RAF after the war was over. In other cases the sons of WWI servicemen either joined the RAF or enlisted with them after the outbreak of war in 1939. John Nicholas Haworth, CB, DSO, DFC and Bar (1912-1974), was born in Buenos Aires. His father, Lieutenant Walter Whitworth, spent part of his life in Argentina but was domiciled in Radcliffe during WWI with his family at the home of his wife’s sister. He lost his life in 1918 fighting with the 1/7th Lancashire Fusiliers. Both his sons joined the forces as adults. John had a long career in the RAF which he joined in 1930 at the age of eighteen, rising to the position of Air Commodore. In 1943 he was station commander at RAF Scampton, the operational base for 617 Squadron and Operation Chastise. He was technical adviser for the 1950s film The Dam Busters and was portrayed by Derek Farr. After the war he remained in Lincolnshire at RAF Swinderby (1951-1953) then later became Chief of Staff of the Ghana Air Force (1961-1962).

Although aircraft and safety standards had improved significantly in the RAF by 1939, WWII saw tremendous casualties in the service numbering around 70,000 personnel (about eight times as many as in WWI) with a concentration of deaths in Bomber Command. One of those to lose his life while serving with the RAF was Samuel Edward Pike, born 1920 and known as Ted, son of Fred Pike who served with the RNAS.

Ted Pike with parents Harriett and Fred in 1942

Photograph with kind permission from Ted’s daughter.

Ted was brought up in Brielen House, Brielen Road Radcliffe on Trent, built by his father and named after the place his Uncle Charles was buried in France. He trained at RAF Cotfoss in Yorkshire and was then transferred to RAF Dyce (now Aberdeen airport), 404 Squadron, in July 1942. He was killed on 5th December 1942 in a flying accident while acting as a Navigator and Wireless Operator with the Royal Canadian Air Force, which had squadrons based at Dyce. He was flying in a Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter. His wife had recently given birth to his daughter who was just five weeks old.

His body was brought back to Radcliffe by train and left in sidings overnight opposite his parents’ home, Brielen House. His sister was allowed to stay in the carriage all night. An RAF band accompanied his coffin from Radcliffe station to St Mary’s Church where the funeral took place. The practice of military bands at funerals for officers and airmen who die in service with the RAF continues today as does pride in the legacy of former comrades.

Rosemary Collins

To read more about these RAF servicemen click below:

Charles Claye, William Ecob, Henry Marshall, William Ritter, Norman Saward