Field Punishment Suffered By

Radcliffe on Trent Servicemen

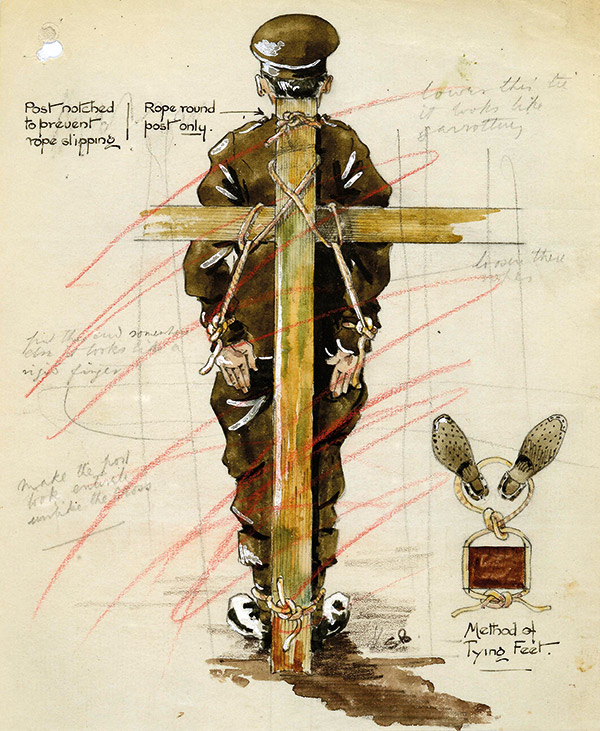

Field Punishment No.1 from a War Office illustration, 1917

A few hints on how to make soldiering easy … Never get drunk or do anything that is likely to get you to the orderly room with your hat off, that is to say as a prisoner as it is far easier to get into trouble than out of it in the army. Mark my word, No 2 or No 1 Field Punishment is not anything you would enjoy.

(From a letter written by Joe Sudbury, sent to his younger brother Herbert when he enlisted.)

Flogging was the British Army’s traditional method for punishing the troops. It was cruel, publicly humiliating, and could result in death of those subjected to the lash. Despite calls for its abolition in the 1830s on the grounds of cruelty and as part of the general trend towards moral reforms, a vote in parliament was heavily defeated after members were influenced by the Duke of Wellington’s demands for its retention. It was not until 1881 that flogging in the British Army was legally abolished by Gladstone’s Liberal government and replaced by Field Punishment Number 1 (F.P.1) and Number 2 (F.P.2); it remained in force in the Indian Army for Indian soldiers until 1920.

Field punishments 1 and 2 were used throughout the First World War. Military discipline, underpinned by various punishments including F.P.1 and F.P.2, was a crucial factor in ensuring compliance and maintaining the imposition of terrible conditions. Field Punishment Number 1 meant the convicted man was publicly shackled in irons and secured to a fixed object (see illustration). Rules stated he should only be fixed for up to two hours in twenty-four, and no more than three days in four in his sentence. Field Punishment Number 2 was similar except the man was shackled but not fixed to anything and could therefore march under restraint. A Commanding Officer could order field punishment of up to twenty eight days and a court martial could impose it for up to ninety days.

Although only a small percentage of those who enlisted endured field punishment, there were still 60,210 cases of F.P.1 and around 27,000 cases of F.P.2 during the First World War. The frequency of and reasons for the use of field punishment is illustrated here with reference to Radcliffe on Trent servicemen. Military details have been collated for over 400 servicemen (see the Radcliffe on Trent Roll of Honour). Only ten of these men are known to have been subjected to Field Punishment No. 1 or 2. A further seventeen men received other forms of punishment (deprived of pay, confined to camp, loss of rank). The offences of ten of these seventeen, who were often older men over the age of thirty, took place in the U.K. and were typically being absent without leave and being drunk. The remaining seven men’s offences took place in France and did not result in field punishment: they included being absent without leave (ten days loss of pay), reporting sick without cause (seven days loss of pay) and giving the wrong name and number (twelve days arrest).

Field punishment number 1 was ordered for four Radcliffe on Trent servicemen and number 2 for five men. Their cases illustrate the British Army’s reasons for administering the punishment. Three of the four Radcliffe men who received F.P.1 were regular soldiers, all of whom had enlisted ten years before war was declared and served with the Sherwood Foresters. George Henry Walker of the 1st Sherwoods is the more extreme case; he was subjected to field punishment four times, amounting to seventy days overall. He was given twenty eight days F.P.1 early on in December 1914: when on active service, absent from parading with party to re-join unit at 12.30 pm until 2 pm and returning therewith. He was thirty-two. Three months later he received F.P.2 in March 1915 for fourteen days after being absent from parade when on duty in the trenches, stating a falsehood to an N.C.O. and trying to obtain intoxicant liquor. The following year, two days before the Battle of the Somme, he received twenty eight days F.P.1 for being drunk in his billet about 11.15 pm. The punishment did not modify his behaviour; on 15th October 1916 he received fourteen days F.P.2 for disregarding Battalion Standing Orders and taking liquor away from an Estaminet. Shortly afterwards on 23rd October he was wounded in the thigh and invalided to England. On return to the Front in June 1917, he was transferred to the 16th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters. He was killed in action in August 1917.

George Newham, 2nd Sherwood Foresters, was given eight days Field Punishment by his C.O. for absence and drunkenness in February 1915. He was thirty. In March 1915 he received twenty eight days F.P.1 for drunkenness; there were no further offences from that point onwards. He was wounded twice after his punishment and then became a prisoner of war in 1918; he was discharged with a ‘fair’ character and awarded a disability pension of 45% for life. Charles Tytherley, also of the 2nd Sherwood Foresters, was awarded seven days F.P.1 for absence in December 1914. he was killed on the Somme in October 1916. Lance Corporal Albert Vickerstaff, who was in the Territorials before the war and transferred to the Machine Gun Corps in 1916, received three days F.P.2 in December 1916 for being absent from parade. He then received fourteen days F.P.1 in June 1917 for insolence to an N.C.O. He was later promoted to Corporal and became Sergeant in October 1918. The arbitrary imposition of field punishment is exemplified by comparing his case with the offences committed by Private George Doughty, Royal Field Artillery. In February 1915 George was sentenced to undergo 56 days detention for failing to appear at the place appointed by his C.O. and using insubordinate language and violence to his superior officer. In 1916 he was deprived of ten days pay for injuring a mule.

Five young Radcliffe servicemen who were all volunteers or conscripts received F.P.2 for various or unstated reasons. Arthur Young from the Lincolnshire Regiment received ten days F.P.2 in September 1915 and Alfred Upton from 1/7th Battalion, Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) received two days F.P.2 in February 1917. Within days Alfred Upton was transferred to another West Yorkshire battalion and hospitalised for illness. Both men were later killed in action. Three other men receiving F.P.2 survived the war. Frederick Bemrose of the Royal Garrison Artillery received four days F.P.2 for not complying with battery orders in the field. George Doughty, Royal Field Artillery, was awarded ten days F.P.2 in May 1915 for injuring a government mule in the field. Harold Barratt, Royal Field Artillery, was awarded four days field punishment no.2 by his C.O. (Lt. Col. L.T.C. Ward) for failing to pay compliment to an officer on 3.12.18 – a month after the armistice.

Questions began to be asked in the U.K. about field punishment following an article written by social reformer Robert Blachford in 1916. In response, General Haig argued that the punishment was necessary because the stigma provided a good deterrent and without it men would lack moral fibre. From 1917 field punishment Number 1 became less severe after clearer instructions were issued by the War Office regarding how the ropes should be tied and the length of time men should spend being tethered. It has been suggested that on occasion offenders were tethered in stress positions, experienced their punishment close to enemy fire and some were later deliberately placed at the fore-front of assaults on enemy lines. Field punishment Number 1 was abolished in the British Army in 1923.

Rosemary Collins, September 2016