Radcliffe on Trent remembers the

South Nottinghamshire Hussars

The South Nottinghamshire Hussars parading in Nottingham Square, 1914

Courtesy of RNLY Museum

The First World War saw the introduction of industrial warfare on a large scale. Technological innovations included the scaling up of production of heavy guns, use of tanks in theatres of war, expansion of air services, extensive use of submarines particularly on the German side and deployment of chemical weapons in the form of poisonous gases. Behind the new developments stood the staple of war that had served armies for centuries – the horse. As the war unfolded it became apparent that the British Army could not function without its horses and mules: more than a million were deployed. By 1918 half the horses and mules were transporting supplies, equipment and the wounded. Around 100,000 ‘riding horses’ were being used by soldiers behind the lines for reconnaissance and carrying messages, 90,000 gun horses were working in teams and 75,000 were kept as cavalry horses (source: www.bbc.co.uk ‘Who were the real war horses of WWI?’). Army horses were treated with great care but sadly around half of them perished, largely from disease and exhaustion. Over the course of the war Britain lost more than 484,000 horses: one horse for every two men.

When the war began in 1914, there was a difference of opinion between the older senior cavalry officers of the Boer War who felt there was a rightful place for cavalry charges in the ensuing conflict and those who regarded cavalry as already obsolete. The idea that cavalry charges could play a vital role on the Western Front was put to the test in August 1914 during the retreat from Mons. British troops at Mons were confronted with a rapidly advancing German army and by August 23rd their position had become untenable; they were forced to withdraw. On August 24th Captain Francis Grenfell V.C. led a charge, against his own judgement, of the 9th (Queens Royal) Lancers at Audregenies straight into German artillery and machine gun fire before being halted by two lines of barbed wire. The aim was to provide cover for the withdrawal of the troops. Although the charge did provide extra time for the retreating army, casualties were high among the Lancers and their horses. Captain Grenfell survived, wounded, but was killed the following year at the Battle of Hooge. Infantry units were also present at the charge providing defensive cover. The 1st Cheshire Regiment suffered greatly, losing 80% of its men: 777 were killed in action out of a total strength of 977 while only 40 of the surviving men from the battalion remained unwounded. Once trench warfare was established in the autumn of 1914, the role of cavalry charges on the western front was restricted.

The First Victoria Cross of the European war, 1914. Captain Francis Grenfell, 9th Lancers at Audregnies, 24 August 1914

by Richard Caton Woodville (1856-1927)

Image from the National Army Museum online collections, reproduced here via a Creative Commons licence.

Horses were requisitioned by the Remount Squadrons for general war service immediately after the outbreak of war and male recruitment into cavalry units was brisk. In Nottingham, for instance, the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry (South Nottinghamshire Hussars) was advertising in the local papers for recruits ‘with previous service in a mounted unit’. The Nottinghamshire Yeomanry (South Nottinghamshire Hussars) was formed in Nottingham in April 1908 as part of the new Territorial Force and was placed under the orders of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Mounted Brigade, 1st Mounted Division. It became the 1/1st in 1914 when the territorial force created its second-line units and then came under the orders of the 2nd Mounted Division in September 1914. The Nottingham Evening Post reported on September 11th that over 70 of the 120 men required for the active service battalion had been recruited, all with experience. The Nottingham Journal,

September 26th, announced that Colonel Trotter, C.O. of the South Notts. Hussars was forming a squadron in the Reserve Regiment composed only of young farmers and that several had already joined. On the same day the Nottingham Evening Post reported that recruitment had been so positive ‘that it was decided not to accept those who were not good horsemen’. One Radcliffe farmer who enlisted was William Brewster Haynes. He trained with the Hussars in England but was then commissioned into the Royal Field Artillery and left with them for France in April 1915.

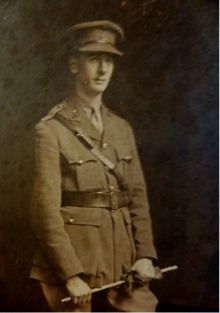

Another young farmer who enlisted in September 1914 was Eric Pell (pictured left) who was working on a farm at Holme Pierrepont at the time. Eric was to enter the Balkans theatre of war in November 1915. By this time the 1/1st South Notts Hussars had seen over six months of service in the middle east. In April 1915 the hussars had sailed from Avonmouth to Egypt as part of the 2nd Mounted Division. The South Notts Hussars were attached to the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Mounted Brigade within the division. On arrival in Egypt the five brigades of the division were split up and stationed at Alexandria, Cairo and Ismailia on the Suez Canal. In August the division was dismounted. The horses were left in Egypt under the care of two troops while the brigades of the 2nd Mounted Division were transferred to Gallipoli where they served as infantry until December 1915. The South Nottinghamshire Hussars were awarded battle honours for their actions at Suvla and Scimitar Hill. The Division was then evacuated from Gallipoli and returned to Egypt where it was reformed and remounted; it is assumed that Eric Pell joined them at this point (information on his service record is incomplete).

Another young farmer who enlisted in September 1914 was Eric Pell (pictured left) who was working on a farm at Holme Pierrepont at the time. Eric was to enter the Balkans theatre of war in November 1915. By this time the 1/1st South Notts Hussars had seen over six months of service in the middle east. In April 1915 the hussars had sailed from Avonmouth to Egypt as part of the 2nd Mounted Division. The South Notts Hussars were attached to the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Mounted Brigade within the division. On arrival in Egypt the five brigades of the division were split up and stationed at Alexandria, Cairo and Ismailia on the Suez Canal. In August the division was dismounted. The horses were left in Egypt under the care of two troops while the brigades of the 2nd Mounted Division were transferred to Gallipoli where they served as infantry until December 1915. The South Nottinghamshire Hussars were awarded battle honours for their actions at Suvla and Scimitar Hill. The Division was then evacuated from Gallipoli and returned to Egypt where it was reformed and remounted; it is assumed that Eric Pell joined them at this point (information on his service record is incomplete).

The South Nottinghamshire Hussars remained based in Egypt until the summer of 1918; their principal role for most of the war concerned campaigns in the Middle Eastern theatres of war where there was a requirement for cavalry skills. The initial objectives of these campaigns were the defence of the Suez Canal, Persian Gulf and Dardanelles which were of strategic importance. The Allies later carried out aggressive campaigns against the Ottoman Empire where the role of the mounted cavalry was to be indispensable.

Radcliffe on Trent men who served with the South Nottinghamshire Hussars in the Middle East include William Vickerstaff who entered active service in September 1915, George Steadman, George Hopewell and Sergeant Charles Ellison M.M. who all served in Egypt at some point from 1916 onwards and Captain Francis Holmes who entered Egypt in July 1917. Samuel Haynes, a married man with children, enlisted with the 1/1st South Notts Hussars in 1915 and remained with his unit until the end of the war. Lack of information or missing service records makes it difficult to ascertain the precise movements of these men.

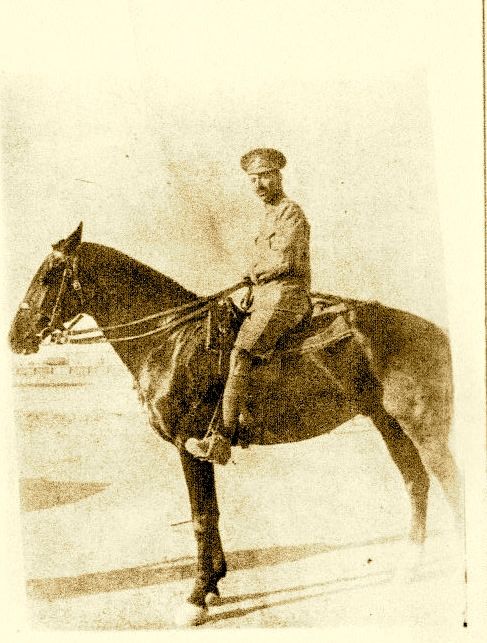

Samuel Haynes in Egypt with his mule Phyllis.

Following the return from Gallipoli the 2nd Mounted Division was broken up. Some units were posted to the Western Front or to other commands. The Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Mounted Brigade (which included the South Notts Hussars) left the division in January and transferred to Salonica in February 1916 where it was re-designated the 7th Mounted Brigade. Operations in Salonica were concerned with the conflict between the Allied forces against the Bulgarian Army and the liberation of Serbia. The 1/1st South Nottinghamshire Hussars were present from February 1916 to June 1917 when they returned once more to Egypt. They received battle honours for their participation in the Struma Offensive in August 1916 which resulted in the shortening of the Macedonian Front. The Balkans was a difficult environment for both horses and men as each suffered from the heat and insect borne diseases.

Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing-Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916

by Stanley Spencer, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

Eric Pell was invalided home from Salonica in September 1916 with heat stroke and malaria. He was later commissioned as Lieutenant in the 11th Hussars in April 1917. Six other Radcliffe on Trent men were in Salonica with the service corps, providing essential support for the cavalry unit. Corporal Henry Richmond, who had been a territorial in the South Notts Hussars before the war, served with the R.A.S.C.

He was a shoeing smith and farrier with skills in treating sick horses. He also suffered from malaria and was eventually discharged to the U.K. where he continued to be affected by his illness. His neighbour from Radcliffe, Thomas Wheatley, who was a fellow blacksmith and shoeing smith, remained in Salonica until December 1918 and was injured falling off a mule. Thomas’s brother Edward, also in the R.A.S.C. and based in Salonica, died of typhoid fever in September 1916 and was buried at Salonica (Lembet Road) Military Cemetery. Reginald Smith (pictured left) and Leonard Rasbeary were with the army service corps providing food for the troops. Francis Duke was with the medical corps and was another victim of frequent attacks of malaria.

He was a shoeing smith and farrier with skills in treating sick horses. He also suffered from malaria and was eventually discharged to the U.K. where he continued to be affected by his illness. His neighbour from Radcliffe, Thomas Wheatley, who was a fellow blacksmith and shoeing smith, remained in Salonica until December 1918 and was injured falling off a mule. Thomas’s brother Edward, also in the R.A.S.C. and based in Salonica, died of typhoid fever in September 1916 and was buried at Salonica (Lembet Road) Military Cemetery. Reginald Smith (pictured left) and Leonard Rasbeary were with the army service corps providing food for the troops. Francis Duke was with the medical corps and was another victim of frequent attacks of malaria.

The 1/1st South Notts Hussars returned to Egypt in July 1917 where the 7th Mounted Brigade was placed under the orders of Desert Mounted Corps. Although by this time considerable changes had taken place on the western front in the tactical use of cavalry, horses were indispensable to British battles in Palestine, particularly under Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, for whom cavalry made up a large percentage of his forces. The Desert Mounted Corps, one of Allenby’s units, was a mixture of Australian, New Zealand, Indian and English Yeomanry regiments from the Territorial Force, largely equipped as mounted infantry rather than cavalry. By mid-1918, Allenby’s forces had defeated the Turkish armies in a series of battles that included the extensive use of cavalry by both sides. The South Nottinghamshire Hussars received battle honours for their engagements in Gaza (1917), Battle of Mughar Ridge (November 1917) and the Battle of Nebi Samwil (also in November 1917) fought during the decisive British victory of the Battle of Jerusalem.

Three further Radcliffe servicemen have been confirmed serving with the British Army in Egypt from 1917. William Howard, who served with the Royal Engineers, had been lodging at Harry Richmond’s home on Mount Pleasant, Radcliffe on Trent, before the war. While in Egypt he cut his hand preparing fodder for his mule; his infected wound necessitated the amputation of one of his fingers. Lieutenant Bernard Sketchley served with the Durham Light Infantry and Sergeant Evelyn Wright, a Caterpillar driver with the army service corps, was afflicted by several bouts of malaria while serving in Egypt.

In April 1918 the 1/1st South Nottinghamshire Hussars were converted to a machine gun corps in response to German gains in the Spring Offensive and urgent need to increase troops on the Western Front. The unit was dismounted to form B Battalion, Machine Gun Corps, merging with the 1/1st Warwickshire Yeomanry. Plans were put in place to transfer the newly formed battalion to France. On May 26th the men embarked on HMS Leasowe Castle at Alexandria on route for Marseilles, France.

Two Radcliffe Hussars are known to have been on the Leasowe Castle: William Vickerstaff (pictured left) and Samuel Haynes. The ship was carrying 2,900 troops plus crew and set off with five other troopships convoyed by Japanese destroyers, accompanying sea planes and trawlers. She was struck by a torpedo, fired from German submarine UB51, on the starboard side at 12.25 a.m. May 27th approximately 104 miles from Alexandria. The engines were stopped and the ship remained on an even keel, settling slightly by the stern. The remainder of the convoy had disappeared ahead apart from the Japanese Katsura(‘R’) which remained to help. Troops fell in at their emergency stations immediately. Those berthed on the lower decks had been told to sleep on deck near their stations in case of an attack. Around forty boats and rafts were launched and troops began leaving the ship by ropes and ladders. By 1.30 a.m. about 2000 men had been evacuated.

Two Radcliffe Hussars are known to have been on the Leasowe Castle: William Vickerstaff (pictured left) and Samuel Haynes. The ship was carrying 2,900 troops plus crew and set off with five other troopships convoyed by Japanese destroyers, accompanying sea planes and trawlers. She was struck by a torpedo, fired from German submarine UB51, on the starboard side at 12.25 a.m. May 27th approximately 104 miles from Alexandria. The engines were stopped and the ship remained on an even keel, settling slightly by the stern. The remainder of the convoy had disappeared ahead apart from the Japanese Katsura(‘R’) which remained to help. Troops fell in at their emergency stations immediately. Those berthed on the lower decks had been told to sleep on deck near their stations in case of an attack. Around forty boats and rafts were launched and troops began leaving the ship by ropes and ladders. By 1.30 a.m. about 2000 men had been evacuated.

HM Sloop Lily turned back from the convoy to assist, coming alongside the forecastle of the Leasowe Castle and making fast with ropes. Rescue operations were carried out until about 2.am when the ship sank rapidly at the stern. The ‘Lily’ narrowly escaped going down with her by crew cutting the hawsers that had tied the two ships together. Many men jumped into the sea in the last few moments and were picked up from rafts, including the Battalion commander Major Sir St. J. Gore Bt. However, 102 men lost their lives including eight officers and forty four other ranks from the South Notts. Hussars. Most of the men who died when the ship went down had been waiting on the forecastle. William Vickerstaff was among those missing at sea; his body was not recovered. Other casualties included those who were organizing the evacuation: Colonel Cheape, C.O. of the Warwickshire Yeomanry, Captain Drake, the ship’s adjutant and the ship’s captain, Captain Edward John Holl D.S.C.

Men rescued from HMS Leasowe Castle onto a lifeboat.

Photo taken by a survivor, reproduced by kind permission of survivor’s descendants resident in Radcliffe on Trent

The majority of the men on board were saved. Samuel Haynes was rescued from the sea but his thumbs were permanently damaged as a result of clinging to a raft. The survivors were shipped back to Alexandria – HM Sloop Lily had about 1,100 rescued men on board. The men re-embarked on the 17th June 1918 on HMT Caledonia. Their convoy, consisting of the Caledonia, Kaiser-i-Hind and three accompanying ships, sailed on the 18th arriving at Taranto, Italy, on the 21st. The men entrained for France on the 22nd arriving at Etaples base camp on the 29th June. ‘B’ Battalion, Machine Gun Corps was renamed the 100th (Warwickshire and South Nottinghamshire Yeomanry) Battalion, Machine Gun Corps in August 1918. Those who lost their lives in the sinking of the Leasowe Castle are remembered on the Chatby Memorial to the missing at sea in Alexandria, which commemorates more than 700 Commonwealth WWI servicemen who died when their vessels were attacked.

Servicemen and their horses frequently formed a close bond but most were parted from each other at the end of the war. The British Army had 800,000 horses in service at the time. Only mounts owned by officers were guaranteed a passage home. Among the remainder, the youngest and healthiest horses were brought back to England where 25,000 stayed in the army and 60,000 were sold to British farmers. Many horses in France and Belgium were sold to local farmers while the oldest and least fit were sent to the knacker’s yard. A few of the oldest among that group were rescued by the Horses Trust. In the 1930s the RSPCA and Blue Cross Fund, aided by donations from the public, were able to rescue a larger number of the old horses still alive on the continent and brought them back to retirement homes in Britain (source: www.bbc.co.uk).

The South Notts Hussars are remembered with pride in their county town. Nottingham St Mary’s Church’s several war memorials includes one to the regiment. The inscription, written in gold in the large oval, reads:

In memory of the Officers, N.C.0’s and Men of the South Notts Hussars who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 in Egypt, Gallipoli, Macedonia, Palestine, France.

Books of remembrance are situated below the memorial inscription and lie behind the grill.

The end of the war saw the demise of cavalry regiments. Most were either converted to mechanized units or disbanded; the trench warfare of the Western Front had made cavalry regiments obsolete. The former South Nottinghamshire Hussars were converted to the 107th (South Nottinghamshire Hussars Yeomanry) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. The surviving Radcliffe Hussars did not stay on in the army after the war and returned home. Lieutenant Eric Pell, whose brother Harold was killed at the Somme, went back to the family farm at Flawbourgh, where his descendants still reside. Captain Francis Holmes married a Red Cross V.A.D. and continued his previous employment in the lace industry. George Hopewell moved with his wife to Nottingham and worked as a chauffeur while George Steadman became a locomotive fireman living in Peterborough. Samuel Haynes carried on his former trade as a joiner while Sergeant Charles Ellison emigrated to Canada, married Sergeant M Nash from the Women’s League Mechanical Transport and had an active life as a swimming instructor. William Howard, Harry Richmond, and Bernard Sketchley, who served with the British Army in Salonica and Egypt, had foreshortened lives and died in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Reginald Smith, who also served in Salonica, returned home, married and had seven children. He called his first son Reginald Allenby after Field Marshall Allenby, Commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, who captured Jerusalem in December 1917. Reginald Smith’s son was always known as Allenby and ran a greengrocer’s shop in Radcliffe on Trent as an adult.

Regimental badge of the South Nottinghamshire Hussars

Rosemary Collins