A Personal Account of World War I

by G. V. Elwin

Chapter 1

From Enlistment to the Somme 1914 – 1916

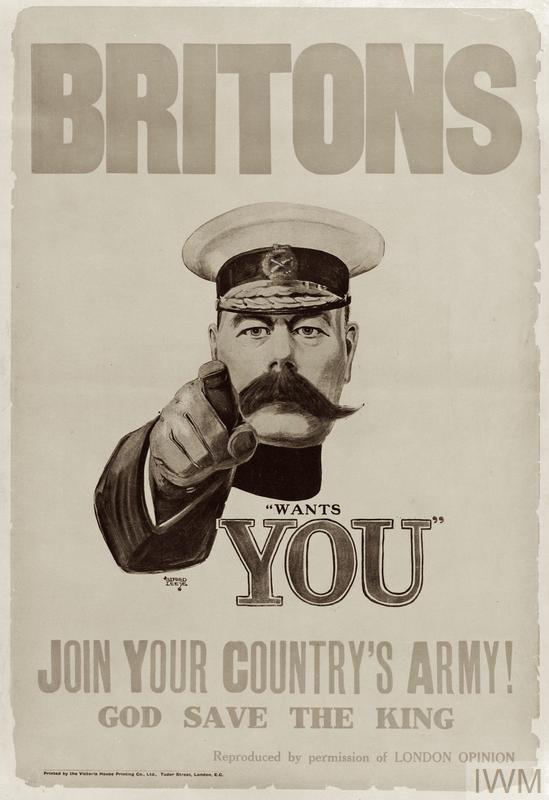

I volunteered for the Army on 4th December 1914 in response to the large poster appearing all over the country saying “Your King and Country Needs you” with the head and shoulders of Lord Kitchener, the Army Chief, pointing an accusing finger straight at the reader. I thus became eligible for the 1914-15 Star medal, given to men joining up before 31st December 1914.

Four of us presented ourselves on that fateful morning at the Mechanics Hall, opposite the Victoria Station in Nottingham. The other three were my elder brother, Harry, two and a half years older than me, 6ft 1½ ins tall, Bert Blatherwick, Harry’s friend, at 6ft 1ins tall and Will Bradbury, Bert’s friend at 6ft 2½ ins tall. I was the shortest of the quartet at 5ft 11ins. I explain all the foregoing because being so tall had a tremendous influence on our ultimate fate. On seeing us the recruiting officer said straight away: “Hello, we want four tall young men like you lot for the heavy artillery to handle the heavy guns”. We were told to strip off our clothes except our shirts and there we stood in line, four tall young men in shirts only. Along came the doctor who gave us a thorough medical examination and passed us as being fit and healthy.

We took the oath to serve the King and Country and various other rigmarole, were given one shilling for that day’s pay; one shilling was an ordinary soldier’s pay at that time. We were told to dress, go home, and wait instructions which would be sent to us by post.

It was a few days later when we received our papers. We were told to go to Newhaven in Sussex by train in the company of a Nottingham Sergeant Major who had been on the Army Reserve and was now re-joining the Army. Sgt. Major Farnell was his name. I remember very vividly the train journey from Nottingham to Newhaven as my three companions and the Sgt. Major played cards, ‘Solo’, all the way of the journey. Solo needs four players, so the youngest, l, did not play. They played for small money stakes and the Sgt. Major won most.

I have omitted the ages of my companions. Harry, my brother as I have mentioned earlier, was two and a half years older than me, Bert Blatherwick was twenty two, same as Harry, and Will Bradbury was the oldest at twenty three. So I was the baby at nineteen and a half.

On reaching Newhaven station we joined other recruits already there and waited for some time for others to arrive. It was quite dark by this time and we were lined up and marched off in the darkness to an Army fort overlooking Newhaven Harbour. It was on a hill top and we straggled up the hillside, through an enormous arched gate which clanged ominously shut behind us after we had marched inside. So our Army career had begun.

Army Training: 1915

Once inside the fort, we were split up with about twenty recruits per barrack room. Our quartet managed to get the same room. The beds were just four legs supporting a wire frame, no mattress, and just one grey Army blanket. What a change for us who were all used to pyjamas, sheets and blankets etc. We stripped down to our shirts and pants, rolled the one blanket around us and slept.

Reveille was at 7a.m. and we were on parade in the barrack square at 7.30 a.m. Then a run down the road in the darkness “to wake you up” as the Sergeant explained, then breakfast at 8 a.m. On parade again at 9 a.m., followed by a route march along the roads leading out of Newhaven into the open country. A good five miles each day. This was the routine for a couple of weeks until the fort was almost bursting at the seams with the continuing arrival of new recruits. A camp of Nissen huts was being built on the hillside and earlier recruits than ourselves were marched off there. They lived under miserable conditions as the huts had no doors on them and the windows were unglazed so wind and rain blew inside. Conditions were so bad that no more men were sent there.

New recruits were still arriving so something had to be done to alleviate conditions. It was a wonderful thing that happened. We were lined up in the main street of Newhaven. There were no motor cars or vans in those days on the roads. Our old friend Sgt. Major Farnell was in charge. He said he would read out names and when we heard our names mentioned we were to “spring to attention” and run “at the double” to stand in front of him. To our amazement our four names were read out first. The secret was out, we were to be billeted on the civilian population. We were to go to Mrs. Chilman’s (I forget the road, in Newhaven) who would provide us with bed and breakfast. Off we hurried and found Mrs. Chilman a homely grey-haired lady living alone. She had one grown-up son who was in the Navy and with his ship on the high seas. Her house was a substantial three-storey semi-detached one. She lived and slept on the ground floor. We had two big rooms on the first floor with one big double bed in each, complete with white sheets, blankets and pillows. Sheer luxury! Talking to Mrs Chilman, the secret of our luxury came clear. Our dear old Sgt. Major had billeted himself in the top floor flat above us and he wanted quiet respectable recruits beneath him, not noisy drunkards.

So life took a happier turn: hot breakfasts and a comfortable bed. Dinners were eaten at the fort. This went on for several weeks. It was too good to last. Recruits were arriving daily. The school and church halls in Newhaven were all taken over. The town and its accommodation were bursting at the seams. Then came the change. We paraded one morning and told we were going to be sent next day to Lewisham, London, to live in empty houses.

We said good-bye to dear old Mrs. Chilman next morning then marched to Newhaven station and took the train to London. Then another march from the London terminus to Granville Park, Lewisham. Granville Park was the name of the road and we were put in No. 44. At this point we lost our Sgt. Major and never saw him again until after the war when he was in a civilian job as a commissionaire in uniform marshalling people waiting to enter one of the cinemas in Nottingham. There were about fifty of us in number 44. Our food was cooked in the back garden by an Army cook. We slept on the floor in one of the rooms with our overcoats and one blanket to keep us warm. No undressing at this time, it was too cold, the house was unheated.

Granville Park Road ran uphill from Lewisham centre to Blackheath at the top. Every day we drilled for hours on Blackheath Common. This went on for about six weeks. It was now March 1915 and still very wintry. Suddenly without any warning we were told we were to go next day to Charlton Park where a camp had been established. Again we had a complete turn-around of activity.

We had spent all of the previous four to five months training on how to fire guns and learning all about them. On arrival at Charlton Park it was no guns but everything to do with horses. The Army was noted at that period as being the best institution for putting square pegs into round holes and this change was a glaring example. The camp was made up of about forty Nissen huts each housing twenty to twenty five men. In addition there were horse lines holding about twenty five horses. The horse lines were comprised of pitched corrugated iron roof with closed ends. Down the centre was a barrier up to the roof. The horses faced each other on each side of the barrier so that one line of horses was completely isolated from the other. The feed mangers were long troughs fixed to the central barrier. Each line of horses had a separate swinging iron bar, suspended by two heavy chains between each horse. These were very thick heavy iron bars which if kicked by one horse swung wildly to and fro and who stopped kicking at once. There were about forty horses under the one roof, twenty each side of the barrier, nose to nose. Each man had one horse to look after, it was enough. The Army pampered horses but not its men.

Charlton Park harness inspection. Image courtesy of the Royal Artillery History Trust

So began a routine which lasted two to three months. Reveille by bugle sounded at 6 a.m., on parade at the horse lines at 6.30 a.m. Then the routine started. Grooming came first when the horses bodies were brushed and cleaned, each leg lifted and the stones and dirt picked out of the hooves which if left would create lameness. Some horses were not used to having their legs lifted up and it was a rather dangerous procedure until they became accustomed to it. After grooming and hoof inspection we had to sponge, with a small sponge we were given, strictly in this order, eyes, nose and dock. Not a very pleasant task to sponge a horse’s bottom. Then putting a halter with a rope on the horse we walked them to a long water trough which had been erected in the street outside the camp. Some drank and some did not. We were told to wet their noses as an inducement. Sometimes this was effective, but not always. Finally I should explain that the horses were of the ‘half heavy’ type, not hunting-type horses. We did ride them bareback, strictly at walking pace each day, along the roads outside the camp to give them exercise. During this time I did pass out in Riding School but of course on light hunting type horses.

We harnessed the horses each day, two horses to each wagon, one horse owner in the wagon seat and the other one riding the nearside horse. We had a whip and a leg iron on our right leg. This leg iron was to protect our leg between the two horses as the wagon shaft rose up and down as the horses stopped and started. We trained as an artillery column, going out most days with say, twenty wagons and about fifty to sixty horses. Into the countryside we went, for miles and miles. A favourite place was Eltham.

At the end of grooming time in the mornings and after taking the horses to the troughs, it was time to feed them. A small bowl of grain had been placed behind every horse. The Feed Corporal shouted the magic word ‘feed’ and the horses thereupon went mad, kicking and stamping their feet. Once the grain was emptied into the food trough a strange silence took place as the horses began to feed. I have vivid memories of all these happenings.

After about three months of the foregoing routine with horses at Charlton Park, we four recruits had a severe shock. My brother Harry was to be posted to France. Here I must explain that it had been brought up in Parliament how disgraceful it was that brothers joining the Army together were being separated from each other. A ruling had been enacted that brothers should not be separated. With all this in mind I at once applied to be sent to France with my brother. The request was granted and my brother and myself left Charlton Park in June 1915, leaving behind the two companions we had enlisted with. We did see them again later in France, but not again until we were all demobilised.

We went by train to Gosport near Southampton, again to an old fort which was serving as a barracks. ln fact, these were two forts and we had a spell in both of them. We dawdled there for several weeks being marched for miles each day to keep us fit. Then one day without warning we were told to pack our kit and were marched with many others to Southampton.

I should explain here that our kit comprised a kitbag containing one towel, a pair of underpants, a pair of socks, knife, fork, spoon, jackknife, razor, housewife (a needle and cotton outfit). We were dressed in khaki riding breeches, jacket, boots, puttees, shirt and pants. Overcoat was a short driver’s coat. Empty leather bandolier across our chests, gas masks tied on under our chin and a steel helmet. The common saying was “A soldier is made to hang things on”. Very true too.

Active Service in France: Autumn 1915

We embarked on a cross Channel ship and when the ship was full and bursting with soldiers, we went across the Channel to Le Havre, the French port, escorted on the way by two Navy destroyers, one on each side of us, but at some distance from us so that we saw them only occasionally.

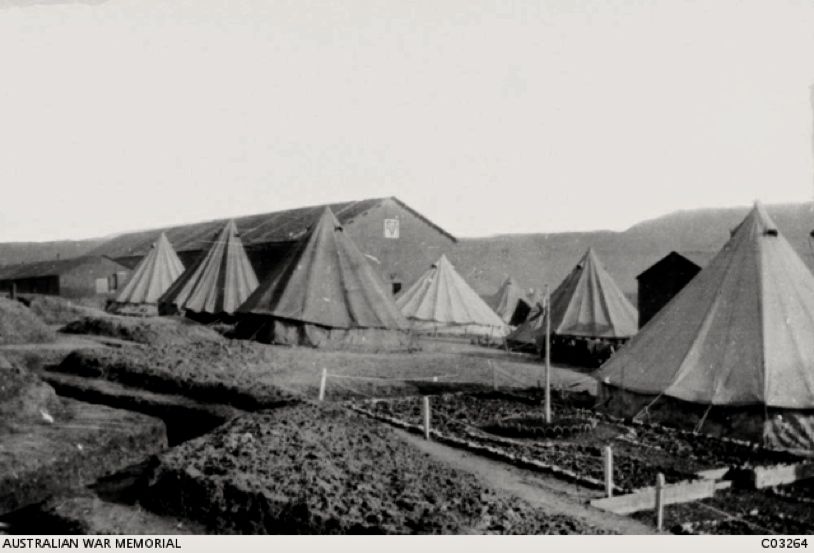

It was dark when we arrived in France and raining miserably. It always seemed to rain in France. We landed in the docks and marched over numerous rail tracks, then up a grassed hillside to an Army camp of bell tents. These tents were probably a good invention fifty years earlier when soldiers numbered hundreds, but not when they were encamped in thousands. Conditions were miserable in the extreme. Six men to each bell tent. Heads just inside the outer rim of the tent and six pairs of feet around the centre pole. It was impossible, of course, and we had to sleep with our knees up all night. lf we touched the tent on the inside when it was raining the rain at once came through the canvas at that spot and dripped rain inside until the rain stopped. Outside, it was squelchy mud tracks between the tents.

Army tents at Le Havre, WWI

We were kept busy, however, being marched down to the docks on many occasions to assist unloading ships. All this went on for several weeks until one day we were given details of the unit we were to join, driven to the railway station and put aboard a slow-moving train. Not, however, in a comfortable seated passenger coach, but in boxed vans clearly marked “8 horses or 40 men”. We sprawled inside on the floor of our van and the train started its long drawn-out journey with many stops and starts. We had the big sliding doors open on both sides to keep the air fresh. Stops and starts scores of times, crawling along, it lasted two whole days. Each time we stopped men dropped off the train and used the side of the track as a toilet. At the start we had each been given two days rations.

At long last we arrived at Bethune, as far as the train could go. We were herded into a large room by the Railway Transport officer, always know as the RTO, about fifty to sixty of us, and he began slowly to read out our names and destinations. He would read out a name and then say “Bus number so-and-so” and each man would then proceed to find his bus number standing outside the station. These buses were London street buses taken over as transport for the troops. We reported to our bus driver that we were to join our battery at a tiny deserted village named “Mazingarbe”. He knew of Mazingarbe and we got aboard and sat inside. All the foregoing was done in the dark. It was about midnight and pitch dark, no moon. The bus had no lights at all and smoking was forbidden. The bus proceeded at walking pace for about 2½ hours dropping men at different points on route. At last it was our turn.

The bus turned off down a road and the bus driver told us to carry straight on and we would come to Mazingarbe after about one mile. We set off walking and the bus disappeared in the darkness. We were all alone, open fields appearing both sides of the road as daylight began to take place. It was about 4 a.m., we came to a ten foot brick wall on our left in which a large hole had been made by shellfire. We heard noises and climbed through the hole and found an Army cook preparing breakfast in a large farmhouse for troops in the empty farmhouse. He gave us each a mug of tea and after a ten minute rest we proceeded on our way. By this time we could see the village, but first we came across a large French chateau which appeared to be some sort of headquarters as a sentry was on duty at the large iron gates to a long driveway. He sent us down the drive to a small side room in the chateau where a soldier sat at a table. We were lucky as it turned out to be our battery’s Brigade Headquarters. They gave us fresh directions and shortly afterwards we arrived at 112 Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery. This was to be our unit for the next three and a half years. By this I mean our unit for we moved to many positions with our guns according to battle requirements.

The sergeant major of the battery saw us first and said the Commanding Officer (C.O.) would see us during the morning. We could see two long-barrelled guns (4.7) alongside an open-sided farm building of the type used by farmers for pushing farm wagons underneath. In this building the gun crew slept and sat about on the floor awaiting targets coming through from headquarters (HQ) when they would instantly spring into action and fire the guns on the target received from headquarters. The targets came through from reports received from the infantry in the trenches, from our balloons in the air or from observation posts in the trenches. They could be German troop movements, working parties, cross-roads activity and so on. It was a continuous procedure day and night.

The Commanding Officer saw us mid-morning. We had been classed as gunners in our early training, but after looking after horses for many months we were now classed as drivers. The C.O was Major J. C. Hanna, an Irishman and a long-serving soldier. He asked what training we had received and then said we would go to the “wagon lines” where the horses were kept. Later in the day he changed his mind and said we would serve on one of the guns as he was short of strong men. My brother Harry was delighted. I was rather nervous and apprehensive. I was only twenty years of age.

Aftermath of the Battle of Loos: Autumn 1915

In the Army’s usual square pegs in round holes, I was put on guard duty the very first night and of course had the worst period from 2 a.m. till 4 a.m., an Army rifle thrust into my hands and told to look out for the orderly officer who would be coming round to test the guard. The rifle was fully loaded with one cartridge in the barrel. lf I heard anything I was to shout “Halt, who goes there!” The orderly officer would reply “Friend” and I had to say “Advance friend and be recognised”, all the time keeping my rifle in a half-firing position. I would then say “Give the password” and he would say something like “Blackpool’, or “Charing Cross”, whatever had been decided upon for that particular night. He would then examine my rifle to see if it was fully loaded, then say goodnight and walk away. I was warned that if the officer asked to be given the rifle for examination I was to refuse; it was not to leave my possession whilst on guard duty, not even for the C.O. himself. So there I was at twenty years of age pacing up and down behind two guns at 2 o’clock in the morning.

German bombardment near Mazingarbe during the Battle of Loos (September – October 1915)

IWM Q58151 French Official photographer

The next day I was involved in my first shoot by the guns. A gun crew was a sergeant and nine men. As a newcomer I was again given the worst job which was to hand out the cartridges one by one as the gun fired. It sounds simple enough and in fact it was simple but also highly dangerous. Each cartridge was about twelve inches long and four inches in diameter and contained about fifty sticks of cordite like thick knitting needles enwrapped in a tubular canvas bag. They were light, easy to handle and came in heavy wooden boxes with screwed-on lids. lf a hot piece of a bursting German shell hit one cartridge the whole lot with me inside would have been burnt to a cinder. I did not like the job but did it for several months until February 1916. By that time I had been in France for six months.

Here I should record an unpleasant experience in which I was involved. In front of our battery was a deserted coal mining village named Philosoph and the main road through the village led to Loos. Our observation post was in the trenches which crossed the Loos road. Remember I was on the guns at this time. A working party of about twenty men with one horse wagon with spades etc. went up the road through Philosoph. From the last house of the village we had to dig in a telephone line six inches deep from house to observation post. The battle for Loos had taken place a little earlier. We started our task in pitch darkness, raining of course, star shells in the sky making us feel very vulnerable.

We soon found the task difficult. We were ankle deep in sticky soft mud, but worst of all, dead bodies lay about everywhere. They were Scots and all wore kilts, a form of dress later discontinued. As usual they were all in grotesque and twisted conditions lying in the sticky mud. A most distressing sight. My brother Harry was in the wagon and received a shell splinter through his soft hat missing his head by a fraction. A very distressing sight for me but repeated several times later on.

Prelude to the Somme: February – June 1916

Suddenly, without warning, my brother and myself were told it was our turn to go on leave to England (February, 1916). It was for seven days – five days at home, two days for travelling. The trip home and back again was uneventful. We enjoyed ourselves immensely. My brother returned to his duties on the gun and remained on that job until the end of the war.

I had a surprise waiting for me. I was transferred from my cartridge job to the Battery Commander’s staff. In effect I was to become a signaller, a telephonist, a linesman, working all the time from the battery up to our observation post in the trenches. It was another square peg in a round hole as I knew nothing of the Morse code or semaphore signalling. There were about twenty of us on the B.C’s staff, a sergeant, a corporal, two bombardiers and the rest signallers.

Now let me tell you about the trenches. There were first and second line trenches with a communication trench leading up to them. The entrance to the ‘com’ trench was usually at the bottom of a piece of hilly land out of sight of the enemy. They were six feet deep, both sides heaped up further with excavated soil. This was the Engineers work. They all had names and at intervals side trenches were cut at right-angles. Our observation post in one battery position was situated in a side trench called ‘Jericho’, the communication trench was called ‘Jerusalem’, obviously named by troops who had originally been in the Middle East. A dreadful spot that was; German machine gun bullets ‘pinging’ overhead all the time. It was certain death to show oneself. Our chaps used to growl: “Oh shut up Fritz. Go to bed!”

Aix-Noulette February – May 1916

When my brother and I returned from England to the battery in February 1916 we found the site empty and deserted. We had no idea where they had gone to at all. That was the end of our Mazingarbe position. We enquired at several headquarters, wandering from one to another until at long last we were told that they were at a village named Aix-Noulette. It was getting dark by this time but at last we found them. It was a small, deserted village and our guns were on the edge of the village. Everything seemed fine, but really as subsequent events proved, it turned out to be one of the worst positions we ever occupied. My brother resumed his position on the guns, whilst I bedded down with the signallers. We were in the kitchen of a small cottage which had a courtyard outside which we had to cross and then over a dirt road to our battery telephone. Previously my companions had dug a small slit trench which housed our telephone. One morning we were cooking our own breakfast with bacon in the fry pan on the kitchen stove. Then the Germans started shelling our battery position. We all dashed out to our slit trench across the courtyard and the dirt track and literally fell into our funk hole, praying we should not receive a direct hit which would have killed all of us. At last the shelling ceased and we went back to the kitchen to find it had received a direct hit, our bacon still on the stove but full of plaster. Blankets, overcoats, towels and most of our kit completely destroyed. It was a frightening experience.

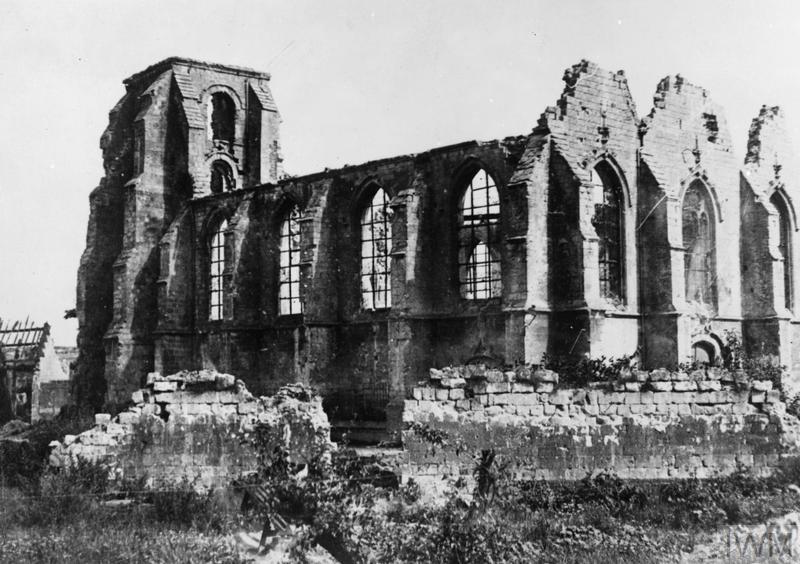

Ruins of Aix-Noulette church

IWM Q61274

About a week later our battery was again severely shelled. The Germans knew just where we were situated and were determined to eliminate us, quite possibly because our one shelling of their position was hurtful. On that occasion one of the German shells burst under the barrels of one of our guns turning it completely over and bending the barrel. Actually it was totally destroyed and unrepairable. As one of the gun crew remarked: “That b***** gun will shoot round corners now”. Our battery cookhouse was installed in a ground floor room of an empty house about 75 yards from us. It received a direct hit one day completely destroying one days rations for all of us. Fortunately the cook was not in the cookhouse.

In all the foregoing incidents we had not a single casualty which was very remarkable. Finally the officers’ quarters were hit and that incident forced a movement and our battery took up another position and left Aix-Noulette for good. We were glad to go. Before leaving that wretched and dangerous position I must record that about three hundred yards to our left rear was Aix-Noulette cemetery. It had been shelled repeatedly by the Germans and coffins and corpses lay all unearthed by exploding shells. I only went there once, that was enough, but it is still vividly impressed on my mind.

Sailly-au-Bois: May 1916

It was about May 1916 when we left Aix-Noulette and went to Sailly-au-Bois on the Somme. We did not know it at the time but that move was in preparation for the great Somme offensive on July 1st 1916. Like everything else I experienced in France, the journey from Aix-Noulette to Sailly-au-Bois was uncomfortable in the extreme. On the evening of our departure and when darkness had taken place our whole battery, comprising of four guns, about twenty four wagons, a couple of hundred horses, 300-400 men, were lined up along the road and commenced our journey. It was dark and raining fitfully. Our kit was in one of the wagons but we still carried our bandoliers, gas masks, haversack, plus other odds and ends. We did not go straight to our new position, it was too dangerous. We went to the rear but at an angle for about ten miles. We trudged along for some ten miles that first night and by daylight we were ensconced in a small wood to escape detection by the Germans. By nightfall and darkness we left the wood and trudged another ten miles to our new position at Sailly-au-Bois. It was a movement I have never forgotten as it was full of incidents, such as wagons and horses getting into the ditch at the roadside when the whole column was halted until the offending vehicle was back on the road.

Bringing supplies up through the mud, 1917. Courtesy of Australian War Memorial, image E00963.

We found Sailly-au-Bois to be a small deserted French village, partly destroyed, and with one main street. Not quite deserted really as two very old French women were living alone in their respective houses. Obviously they had refused to leave their homes, but a few weeks later they were taken away by the French authorities. One woman kept a big pig which she drove through her kitchen to a back room for safety from marauding soldiers each night. When morning came she drove it out again to a small pig-sty outside her kitchen door.

The other woman was more interesting as she kept chickens which seemed to lay plenty of eggs. We used to go to her and say: “Omelette, Madame, s’il vous plait” and she would hold up her fingers asking if we wanted a two, three or four egg omelette. Such luxury! We usually had four eggs. Both pig woman and chicken woman were later taken away much to our regret.

We were to sleep in a large barn with mud walls and upon the hard mud ground inside. We duly put down our waterproof groundsheet, rolled in our blanket, overcoat on and went to sleep. But this lasted only a few minutes as there was a sudden shout of “Rats!” Almost simultaneously a rat ran over the side of my head as I lay on the ground into my next door man’s blanket. He jumped up with a shout and so did everyone else.

We found out next day that the barn walls were full of rat runs and rats were plainly visible during daytime running along their burrows. It was enough for us. Every night we vacated the barn and slept in the orchard adjoining the barn in the open air. We moved out of the barn at night and moved our kit into the barn in the morning. We did this because our sergeant-major said no-one was allowed to sleep outside when covered accommodation was available. He never tried to enforce this dictum, he had done his duty and therefore left us alone. So we all slept outside at night and stored our kit inside by day. I have never forgotten, however, the feeling of that rat running over the left side of my head in the darkness of the barn.

At this time, every day was a busy one, running out telephone lines, helping the gunmen to build emplacements with sandbags, nets with camouflage over the top of each gun; bricks from the villages were broken up to put under the gun wheels so that the recoil of the gun did not dig itself in the soft soil. We had just received two additional guns, making us a six gun battery. This was a major change as it involved the addition of another fifty horses and drivers, another forty gunners and several more officers. We signallers received another ten men to join our party. All, of course, newly trained recruits from England full of theory but no actual experience. We had to teach them the practicalities of war which shocked them.

One day I was walking alone up the main street of Sailly-au-Bois from our barn residence to the battery when I met our Major going from the battery to his sleeping quarters. I saluted and was passing when he stopped me, saying: “Elwin I want to speak to you.” I stopped dead in my tracks, sprung to attention and said, “Yes, sir.” He was about 6ft 3 ins tall and at 5ft 11ins I felt very small. He towered above me. To my utter surprise he then said gravely: “I am going to make you a bombardier”. He then gave me a short lecture on how I should behave, pointing out I should be discreet as I would be ordering old seasoned regular soldiers what to do and what not to do. To all of which I said: “Yes, sir, I understand. I will do my best.” He replied: “I’m sure you will.” Then I saluted again and he walked on.

My head was in a whirl over this sudden promotion over the heads of many older seasoned soldiers. I told our sergeant but he smiled and said he knew all about it as the major had spoken to him first. I sewed the one stripe on my sleeve and my pay went up from one shilling seven pence daily to two shillings seven pence, an increase of one shilling per day. I had always liked our Major, in fact he was very popular with all ranks. Stern, just, but friendly to all ranks under his command. Not like the little poppycock who became our commanding officer after Major Hanna went home for good. Possibly due to age, he had a snow-white head.

So there we were, preparing for the July 1st 1916 Somme offensive. Our village was repeatedly shelled by the Germans and we had to dodge for cover many times, always crouching behind some cover and praying we wouldn’t be killed by a direct hit.

One funny incident stands out in my mind. Outside our barn was a small courtyard with a 20ft well complete with bucket and rope and the usual winding gear. It was our habit to draw up water for washing purposes. One day the shelling started and everyone dived for cover. One of our men, a very nervous Irishman named Mulcahy, jumped into the well bucket and, of course, went to the bottom into the water. Nobody knew what he had done and he spent several hours at the bottom of the well before his shouts for help were heard.